What is Blockchain Governance?

One of a blockchain protocol's most highly valued properties is its level of decentralization. There is usually intense scrutiny of the process for generating new blocks, but less focus on the process for changing a protocol's code.

Blockchain governance is the key here.

While there is no deterministic way of assigning a decentralization score to a given project, some certainly seem to be governed by a larger and more diverse group of people than others. Some may conclude that a large governing body means a more decentralized project.

There have been some attempts at quantifying decentralization.

Metrics such as the minimum Nakamoto coefficient based on the ideas of the Gini Coefficient and Lorenz Curves have been developed to measure decentralization objectively.

The Minimum Nakamoto Coefficient is determined by assigning a decentralization score to the different subsystems of a blockchain:

- Mining

- Clients

- Developers

- Exchanges

- Nodes

- And wallet distribution

... and aggregating those scores into an overall score.

Lets define governance before we dive into the topic:

Governance consists of three questions:

- What should we do?

- Who gets to decide what we do?

- How are deciders chosen and held accountable?

In order to address these question practically, they have to be approached in reverse order:

- First you need to determine how to choose the deciders

- Then choose them

- And lastly, have them make decisions

This makes it sound rather straightforward, but in reality things are a little more complex.

In this article, we want to give an overview of decision making mechanisms used in a decentralized environment.

Choosing the Deciders

In a perfect world, every stakeholder has a say when it comes to how the deciders of a project are chosen. Ideally there would be some sort of fair vote - whatever "fair" means in this context.

Realistically there cannot always be a process to choose the deciders. Most projects in blockchain start with a few like-minded people with an idea of what their ideal cryptocurrency, dApp or blockchain platform should look like.

Oftentimes they find themselves already involved in a similar project.

A project's founding team will then gravitate toward a development focal point. Most often this focal point is a GitHub repository or organization.

As people spend time contributing to a project, they will build a reputation, good or bad, and this reputation is usually how deciders emerge from the group.

People that put in more time, more work, and have better ideas will naturally be recognized as the thought leaders. They will usually take on leading roles in the development process, become repository maintainers or admins.

Once a public open-source project gains momentum and people outside the initial group join, some of them will consequently get involved in the decision making. By supporting a given project, an individual is signaling support for the direction of the project and the project's approach to governance.

Some projects have a process in place for deciding who does and does not participate in decision making. When a form of delegated governance is used, a fixed number of validators or block producers is chosen.

These entities take care of maintaining the blockchain, and have influence on decisions around the code, especially its consensus critical parts.

Decisions in the Early Stages

In the early stages of open-source projects, people with the best reputation and largest social capital will get to make decisions. The people with the necessary backing can, at their discretion, introduce governance processes.

Improvement proposal processes are one example we will look at more closely later on.

In the project's early days, these decisions are usually not very critical as the network has not accrued much real-world value. This is not to say that decisions made at the early stages of a blockchain project cannot be mission critical, but they don't affect an existing user base.

- But what does decide mean anyways?

- What types of decisions typically have to be made in a blockchain project?

There is a wide range of decisions with varying degrees of consequences. Some design decisions include:

- The programming language of the client

- the consensus mechanism

- Block production parameters like block time, block size, etc.

- Support for smart contracts and if so, using which programming language

- Native support for off-chain scaling solutions like sidechains or state channels

Choosing a Consensus Mechanism

An important design decision is the choice of the consensus mechanism, and in case of Proof of Work blockchains, the mining algorithm.

These types of decisions affect the economies of the project, as well as the ecosystem around the protocol. When mining is involved, existing miners with specialized hardware can be approached. Conversely, projects can try to avoid ASICs and choose an algorithm better suited for general purpose hardware.

Most blockchain projects are fundamentally based on Bitcoin's code, and Horizen is no exception.

After code is forked, it is modified according to new design decisions. Extending the core client with useful libraries or APIs will increase the attractiveness for developers and users. Decisions on how to extend and enhance the initial release code will mostly be made by those with social capital.

If a project is built from scratch, there are additional decisions to be made. For example, the blockchain client or deamon's language will influence the type of developers the project will attract.

The above decisions mostly affect new projects, but what about projects with an ecosystem and a history of performance?

Discussing all types of decisions would blow the scope of this article, but one decision has challenged the decision makers of all projects:

How do we scale?

Deciding How to Scale

The best examples of this decision type are most likely the block size limit controversy in Bitcoin from 2015-2017 as well as the scalability discussions in and around Eth2.0.

As we said earlier, it is hard to create a "decentralization score" for a public blockchain, but can we come up with a desirable level of decentralization necessary for any public network?

This is a tough question and the short answer is no.

Depending on the use case, different levels of decentralization are required. For a network mainly providing verifiable scarcity of in-game artifacts, decentralization is arguably less important than a protocol providing a global store of value.

The robustness of a system is proportional to its points of control. A single point of control leads to a single point of failure and low robustness, whereas many distributed points of low influence lead to more robust systems.

On the other hand, fewer points of control lead to faster decision making and greater adaptability to external stimuli. As stated before, the use-case will determine which properties are more desirable.

Different Governance Models

Below we will look at three different categories of governance systems that range from company-like structures in the delegated governance model to the democracy inspired approach of a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO).

Delegated Governance

In a delegated governance model, users vote on a fixed number of delegates.

To give you an idea, large projects using a delegated governance approach have between 21 and 50 delegates. On paper, delegated governance looks similar to representative democracies where the user casts a vote for their representatives, which in turn makes decisions on their behalf.

They differ in that blockchain delegates do not have fixed terms, and the processes for choosing the delegates are not legally binding.

Effectively, projects using delegated governance models often resemble corporate structures more than they resemble community driven open-source projects. The relatively small number of delegates enables efficient collaboration, but also had drawbacks of centralization.

Most delegated governance systems prefer performance over robustness.

In the end, users vote with their time and attention on projects they find valuable.

Decentralized Governance

Bitcoin is the prime example for decentralized governance because its ecosystem grew organically, it had the most time to evolve, and had minimal attention at launch.

The Schelling point for Bitcoin development is the Bitcoin Core GitHub repository. If we adhere to the classification suggested by Schneider, this makes the GitHub repositories of a blockchain project the political focal point.

Repository maintainers have to sign every contribution with their PGP keys. Only contributions signed by one of the trusted maintainers can be merged into the main code base.

This prevents people with extended access to the repository, such as GitHub employees, to insert malicious code without being noticed.

While this process does not make the security system perfect, since PGP keys can be stolen, security is certainly enhanced.

Another principle used to increase the security of the political process is the principle of least privilege, an important concept in computer security. It describes the practice of limiting each user's access rights to the very minimum that is required for them to do their work.

Bitcoin doesn't have a formal specification because no central authority defines what the system should do. Formal specifications are used to describe a system, to analyze its behavior, and to aid in its design by verifying key properties of interest.

If one had to find the closest thing to a formal specification for Bitcoin, it would be the code of the Bitcoin Core repository.

Voting in Bitcoin

There are two types of voting mechanisms that have been used in the Bitcoin ecosystem thus far.

The first mechanism used the version field in Bitcoin block headers, introduced with BIP-0034. It was used to upgrade the system three times, from version 1 to version 4. This mechanism is currently deprecated.

The function behind it was called IsSuperMajority() or ISM for short. Miners used the version data field to signal readiness for backward compatible code changes, or soft forks. Once 950 out of the most recent 1000 blocks signaled acceptance of proposed changes by incrementing the version number, the changes were activated.

Going forward, all blocks with a lower version number would be orphaned.

An updated process was implemented using version bits described in BIP-0009.

Version bits extend the idea of the version data field. The data field in the version bit system is interpreted as a bit vector instead of a simple integer. Each bit in its bitwise representation signals the acceptance of a soft fork, or lack thereof.

This allows up to 29 soft forks to be proposed concurrently.

If we were to apply Schneider's logic to this process, this would mean that "political" suggestions from developers are decided upon by the "fiscal power" of miners. Once a decision is made, the nodes on the network enforce the new rules in their role as the administrators.

Ascribing miners the role of wielding the fiscal power feels like an inaccurate comparison in this specific context.

Generally speaking, it is hard to apply terminology from existing governance processes to blockchain projects. Blockchain operates differently than most systems, hence it is necessary to come up with new processes and new terminology.

An innovative and experimental governance approach enabled through blockchain technology is the Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO).

DAO - Decentralized Autonomous Organization

The Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO) is an entity governed by rules written into the code. It acts predictably according to a predefined "constitution" and is controlled by its shareholders.

Horizen EON is our first public proof-of-stake sidechain and a fully EVM-compatible smart contracting platform that allows developers to efficiently build and deploy dapps on Horizen, while fully benefiting from the Ethereum ecosystem.

Shareholders have the power to change the rules of the DAO, but only if making changes to them was foreseen and enabled at the DAO's inception. Rules might just as well be hardcoded, without the option to adapt them later on.

Interactions with a DAO are tracked with timestamps and digital signatures recorded on-chain. The general concept was introduced as a decentralized autonomous corporation (DAC) in an article by Dan Larimer in 2013. Vitalik Buterin went one step further and proposed that human management could be made obsolete if the smart contracts governing the DAO were written in a turing complete language.

Building a DAO is no simple endeavor. The code governing a DAO is public and anyone can review it. This also means anyone can analyze the code to find potential vulnerabilities. Fixing the code after launch is difficult, as any decision related to rule changes is subject to building consensus.

The most notable attempt at creating a decentralized autonomous organization was The DAO on the Ethereum blockchain. It was launched with $150 million of assets under control in 2016 as a venture capital fund and immediately got hacked.

About $50 million in crypto assets were stolen by the hackers. The hack was reverted by reorganizing the Ethereum blockchain, which led to a chain split. The Ethereum Classic chain is the Ethereum chain where the hack was not reverted, while investors on the Ethereum chain were refunded their assets.

Decision Making Processes

Decision makers can follow many processes to come to a consensus - and one of the most widely used processes is the improvement proposal.

Proposal systems come in different flavors and vary to some degree, but the general idea remains the same.

The Improvement Proposal Process

Improvement proposals processes are mainly a formalized way of suggesting changes and handling those suggestions from idea to activation. Many blockchain projects have developed their flavor of this process:

- Bitcoin's BIPs

- Ethereum's EIPs

- Zcash's ZIPs

- Horizen's ZenIPs

... are among them.

Aragon, a platform specifically built to provide organizations with blockchain based governance tools calls their version Aragon Governance Proposals or AGPs.

Following the improvement proposal process is usually not mandatory for suggestions, but using the XIP process will increase a community member's chances of being considered. This is especially true for contributors without a track record of valuable contributions.

Making Decisions a Reality

Now that we've covered three initial questions:

- How deciders are chosen?

- Who gets to decide?

- And what is done?

... We need to look at how agreed upon changes are implemented. The biggest variable to consider is whether or not the changes are downward compatible, a soft fork or non-backward compatible, a hard fork.

Soft Forks

Soft forks are backward compatible upgrades, think a WhatsApp update. Just because your friends run the latest version you can run an older one and still be able to chat with them.

A soft fork can be triggered either by:

- The users or nodes - a user activated soft fork - UASF

- Miners in a miner activated soft fork - MASF

UASFs

The most notable example of a user activated soft fork was the activation of Segregated Witness (SegWit) on the Bitcoin blockchain. SegWit fixes transaction malleability and increases the block capacity.

It had long been discussed with a non-significant amount of opposition, especially from miners, before a contributor eventually forked the Bitcoin Core client, built the Bitcoin UASF client, and made it publicly available.

The new client gained traction and created pressure on miners to adopt the changes.

After a certain date, the Bitcoin UASF client would have rejected blocks by miners that refused SegWit. Miners are only paid for producing valid blocks - by not upgrading to SegWit they would have risked having their blocks rejected by the majority of nodes.

This could have led to a contentious network fork.

Miners considered the threat to the network's utility, and hence value, serious enough to follow the majority of nodes and activate SegWit. An important learning at that time was that the miners influence on the network can be overruled by its users when users form a strong consensus.

MASFs

In a miner activated soft fork, the block producers signal their readiness for an update by including some metadata in the block headers. BIP-0034 introduced this concept on the Bitcoin blockchain.

The initial mechanism for MASFs had miners increment a blocks version number to support a soft fork. Once 95% of the most recent 1000 blocks would signal the readiness to upgrade, all blocks with the previous version number would be rejected.

This initial mechanism was updated to use version bits instead of the version number. By interpreting the individual bits of the nVersion data field in the block header as a bit vector, a single block header can signal acceptance or rejection for up to 29 forks at once.

When a sufficiently large share of hash power has signaled readiness for a fork, full nodes will enforce those rule changes accordingly.

Hard Forks

A hard fork is a downward incompatible upgrade to a blockchain, think a new Playstation. With your old console you won't be able to play the new games developed for Playstation 4.

The two most notable hardforks in the blockchain space have been:

- The Ethereum and Ethereum Classic hardfork

- The Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash hardfork

Bitcoin Cash increased the maximum block size in an attempt to make the network more scalable. The original Bitcoin client won't recognize these larger blocks as valid, hence it is backward incompatible.

In the case of the Ethereum hardfork, the two versions didn't share a common transaction history, hence the incompatibility.

Horizen Governance

Now, that we have established an understanding of the most important concepts around blockchain governance let us take a look at the governance within the Horizen ecosystem.

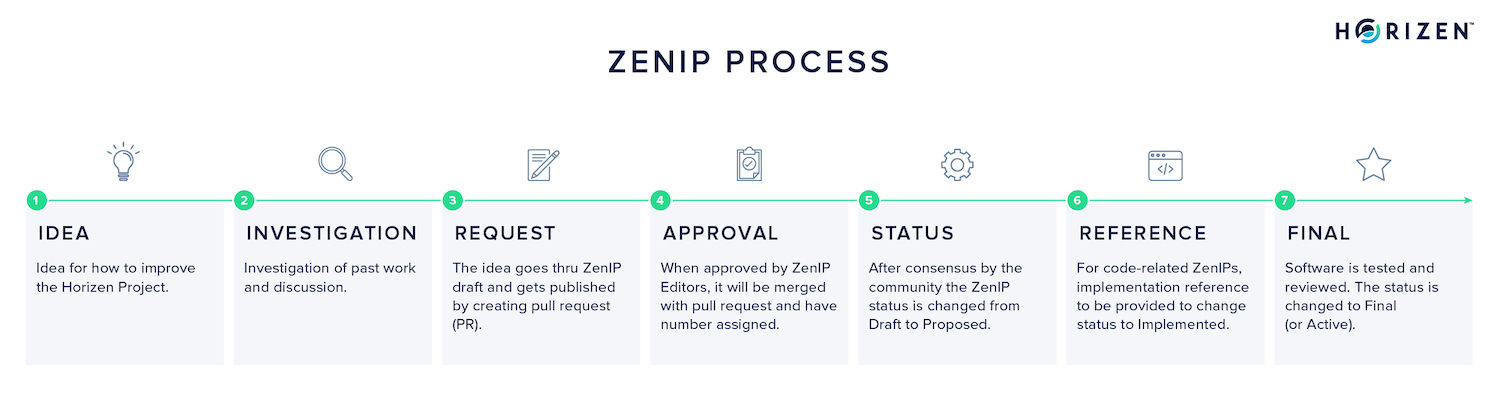

The ZenIP Process

From the very beginning Horizen envisioned a decentralized platform where the infrastructure, funding decisions, and decision making were all decentralized.

Introducing the ZenIP process was an important step towards a decentralized decision making process. Similar processes have proven to work well for decentralized projects, hence it was considered the best way to distribute influence and power towards the broader community.

ZenIPs are meant to standardize the process of suggesting major changes to the Horizen code base and ecosystem as a whole. A ZenIP in and of itself is a document that describes a new feature.

It explains the rationale behind the proposed idea and elaborates on why certain design decisions were made. Each ZenIP starts with an Owner proposing a new idea in the form of a ZenIP. After investigating if the idea is original and if it has chances of being accepted, the idea is put in the form of a ZenIP.

The document needs to contain an abstract, a section about the motivation for the proposed change, a specification, as well as a reference implementation. The draft is publicized by creating a pull request against the ZenIP GitHub repository.

Editors act as the repository maintainers and there are currently three of them:

- One representing the Zen Blockchain Foundation

- One representing the Horizen Community Council

- And one for Horizen Labs

They merge the pull requests in draft status when they deem the document complete. Once there is rough consensus on the ZenIP and the document is completed, the status can be changed from Draft to Proposed by a supermajority of editors.

Next, the status of code-related ZenIPs is changed from Proposed to Implemented once the Owner provides a reference implementation of the proposal. A ZenIP becomes Final when it is activated on Horizen's mainnet.

A Process or Informational ZenIP may change status from Proposed to Active when it achieves rough consensus on the forum or the pull request. Such a proposal is said to have rough consensus if it has been open to discussion for at least one month, and no person maintains any unaddressed substantiated objections to it.

We invite you to check out the ZenIP repository, get involved in the discussions around it and propose your ideas to the Horizen community.

The Horizen Treasury DAO

Horizen is dedicated to building a DAO as one of the first sidechain applications. It will enable decentralized, community based governance, especially with regards to resource allocation.

Part of the Horizen block subsidy goes to the Zen Blockchain Foundation treasury, which uses it to fund the development of the protocol, sidechain implementation, marketing and business development.

The basic model of the treasury system is described in a paper written by our research and development partner, Input Output Hong Kong (IOHK) in collaboration with Lancaster University.

The idea of the Horizen DAO is to have stakeholders in the Horizen ecosystem vote on how Zen Blockchain Foundations treasury funds are spent. Anyone in the community can submit a proposal for consideration. Stakeholders can review the proposals and vote.

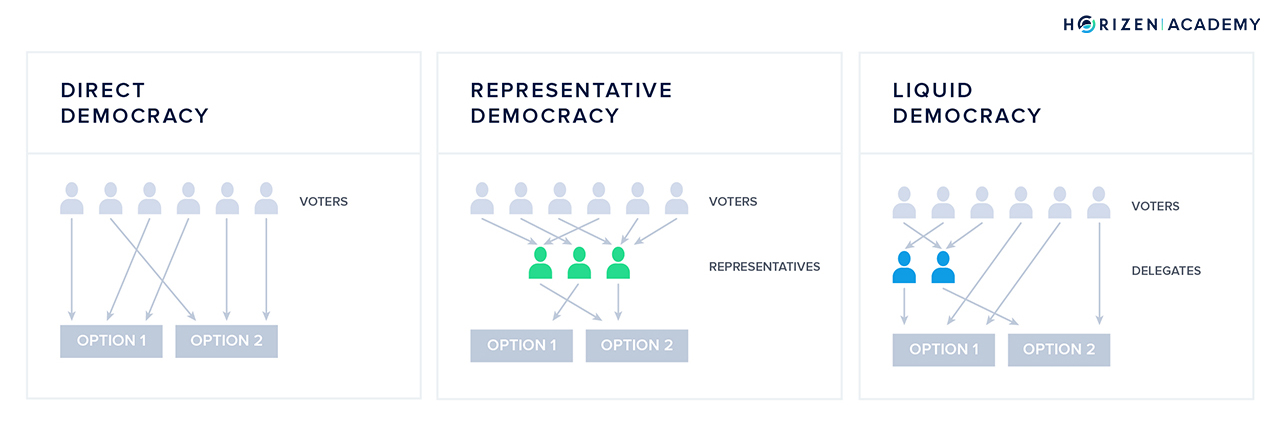

There are many types of voting mechanisms and electoral systems to choose from. The Horizen DAO will use a form of liquid democracy as the mechanism for voting. A thorough discussion of voting schemes would blow the scope of this article.

Still, we would like to outline the core idea behind liquid democracy.

Liquid Democracy

The two existing democratic forms from traditional governance processes are representative democracy and direct democracy.

History's first forms of democracy were direct democracies. They offered their participants fairness, accountability, and control, but they don’t scale well with an increasing number of participants.

Most democracies evolved into representative democracies over time for this reason. While they allow a large number of voters to participate in the decision-making process, there are many issues.

These issues include the transparency of representatives’ votes, accountability of representatives, and high barriers to entry for participants wanting to get involved in the decision-making process.

Liquid democracy can be understood as a dynamic hybrid of direct and representative democracies. It combines many of the upsides of each while doing away with most of their weaknesses. With liquid democracy, you have the option of delegating your vote to an "expert" who represents your views.

A key differentiator of liquid democracy is that you can delegate your vote to whomever you like and withdraw your delegation at any time - making the whole process liquid. This reduces the barrier to entry for people willing to get involved in the governance process and keeps delegates accountable because they can lose delegations at any time.

Alternatively, you can decide to vote on any given issue yourself without involving a representative.

As we said earlier, DAOs are still experimental at this point. There are many unknowns around a DAOs legal status and how to best set it up, as there is little to no precedent of a DAO working for a sustained period of time.

Nonetheless the concept is highly interesting and promises big advancement in terms of social scalability. Thus, we consider it an effort worth making to build a DAO to govern the Horizen treasury.

Summary - Blockchain Governance

Open source protocol governance is something that’s constantly iterated and improved upon. The blockchain space is relatively young, and compared to traditional governance processes so is open source software.

The multitude of blockchain projects represents a huge real-world sandbox. Many attempts at creating fair governance are currently being experimented with, and this constant iteration will improve governance by making it more transparent, efficient and fair.

Arguably, a governance process will never be perfect. Some stakeholders will always see room for improvement even when others are completely in line. It is difficult to determine what perfect means on paper, let alone implementing such a system.

Projects with different goals will also require different approaches to governance. While a global store of value such as Bitcoin needs a conservative approach to governance, new projects working on cutting edge technological advances need faster decision making in order to realize their goals.

Governance needs to be project specific, accounting for the goals and the existing community. Time will tell what the "best" approaches to governance are in the open source arena.