What are Payment Channels?

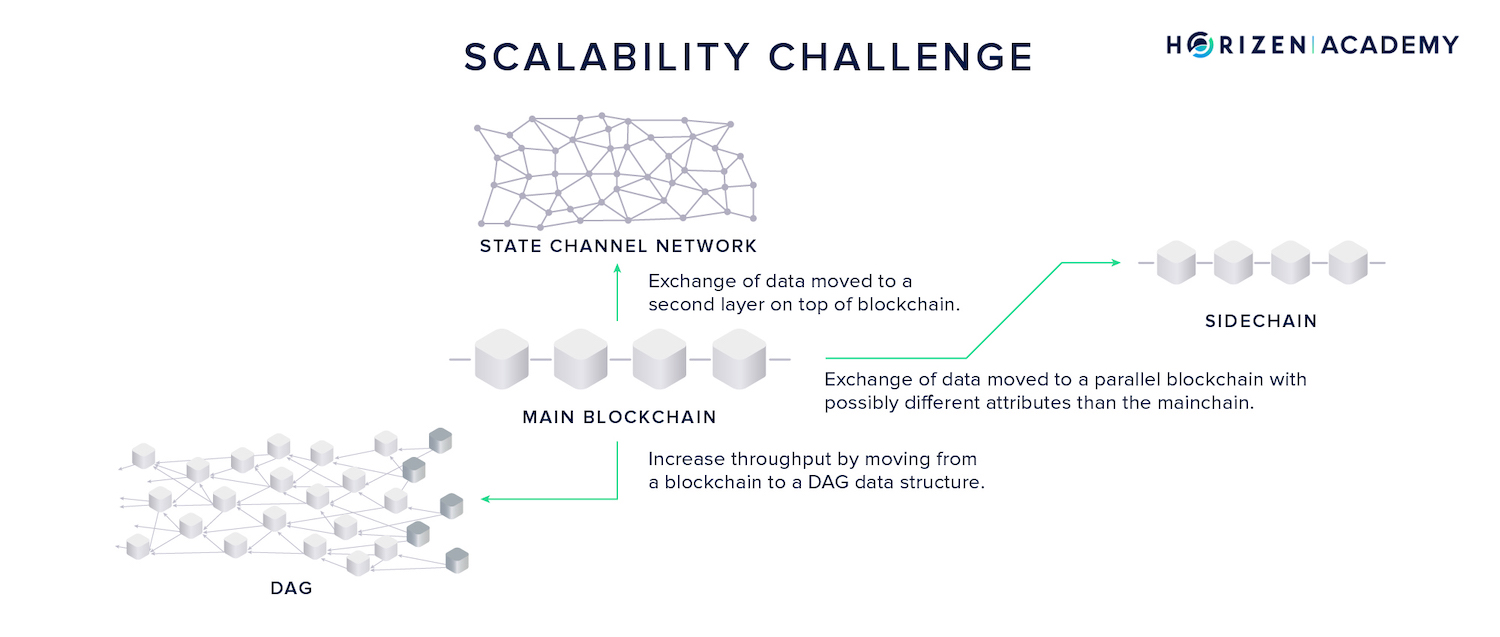

A common criticism of blockchain technology is that it doesn't scale in a decentralized setting and therefore is not able to support mainstream adoption.

Now there are different ways to scale blockchains and increase their throughput, but what if we can allow for more interaction leveraging the security of existing protocols with the capacity we already have available?

Meet layer-two transactions on payment channels.

We introduced sidechains as a scaling approach that spreads the workload otherwise performed by a single set of mainchain nodes to several sets of nodes, each responsible for their sidechain.

We also talked about Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) that hold the potential to dynamically adjust the on-chain, or "on-DAG", throughput by introducing a new type of data structure supporting two-dimensionality in an otherwise mostly one-dimensional blockchain world.

We will cover another highly promising approach to make blockchains security promise accessible to a more substantial user-base - payment channels.

The general idea of payment channels is as follows:

- Two users place funds in a payment channel

- Now, the participants can send funds back and forth within the channel by exchanging signed transactions that are not broadcast to the blockchain.

- When, and only when, participants are done transacting do they use the blockchain to settle their current balances in a channel closing transaction.

- They can exchange an arbitrary number of transactions while placing only two on-chain: The channel opening and closing transaction.

Payment channels are no trivial topic, and many different projects are working on them. To cover the process from opening a channel to updating its balance and lastly closing it, we will focus on the best-known and most active payment channel implementation: the Lightning Network.

What are Payment Channels?

The primitives used to build a payment channel are:

- Regular transactions in the UTXO model

- P2SH addresses, and more specifically MultiSig addresses

- Cryptographic hash functions

- Timelocks

One premise is the construction being trustless by design: You must not have to rely on your counterparty to transact securely.

Whereas the underlying blockchain derives its security from the computational power of its miners in Proof of Work blockchains, payment channels derive security from economic disincentives.

Namely, when one party tries to cheat, the other party will be granted all the money within the bilateral channel. This mechanism allows participants to consider updates to the channel as "final," although only computed locally.

Payment Channels are MultiSig Addresses

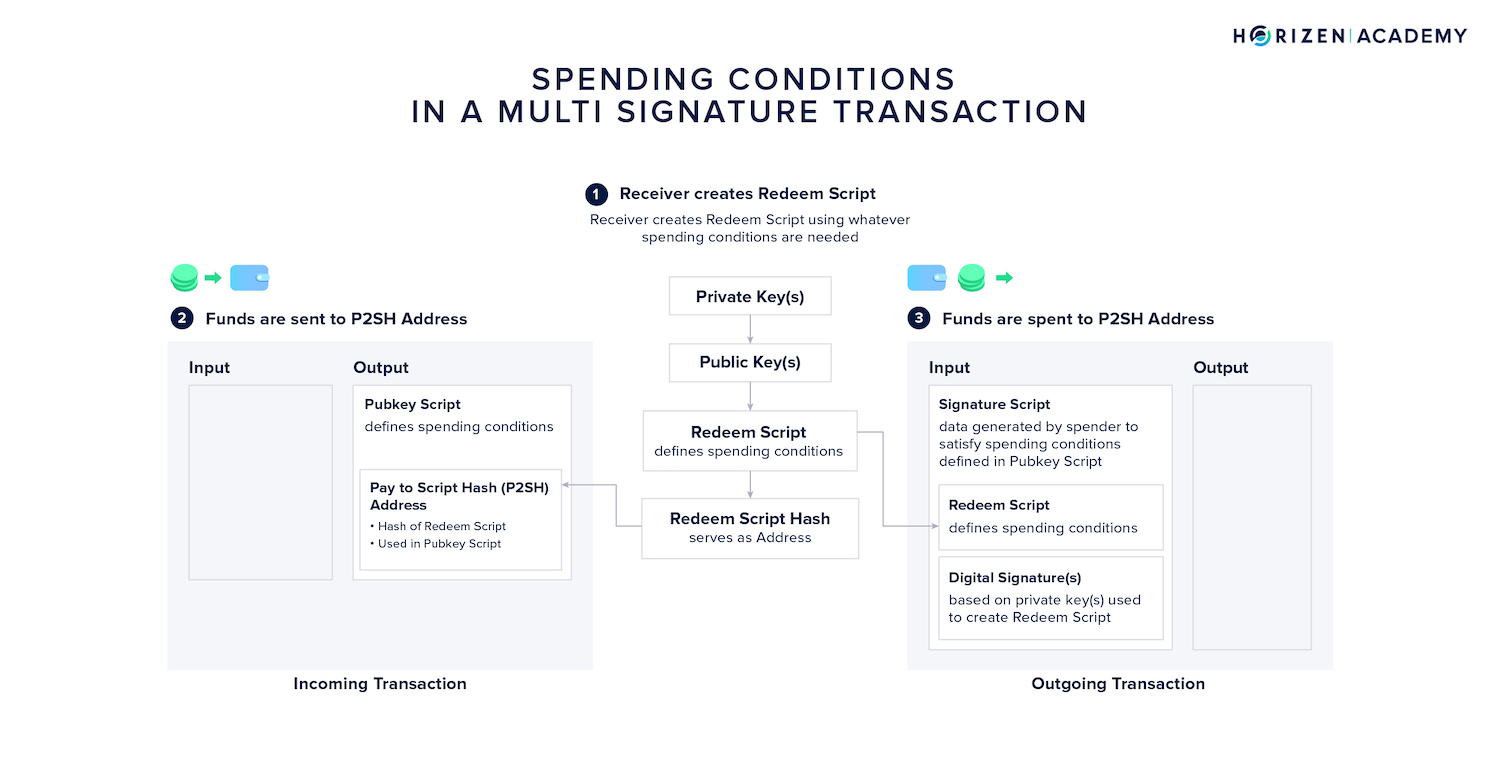

Simply speaking, a payment channel is a 2-of-2 MultiSig account, or more generally speaking, a Pay to Script Hash (P2SH) address.

This can be understood as a simple smart contract controlling funds, the channel balance, and defining the conditions under which these funds can be spent.

A 2-of-2 MultiSig account is based on two private keys, both of which need to sign a transaction for it to be valid.

The spending conditions for the MultiSig account are defined in the redeem script. The hash of the redeem script functions as the address - a Pay to Script-Hash (P2SH) address.

This address and the information contained in the redeem script comprises the locking script of UTXO sent to the P2SH address.

How do Payment Channels Work?

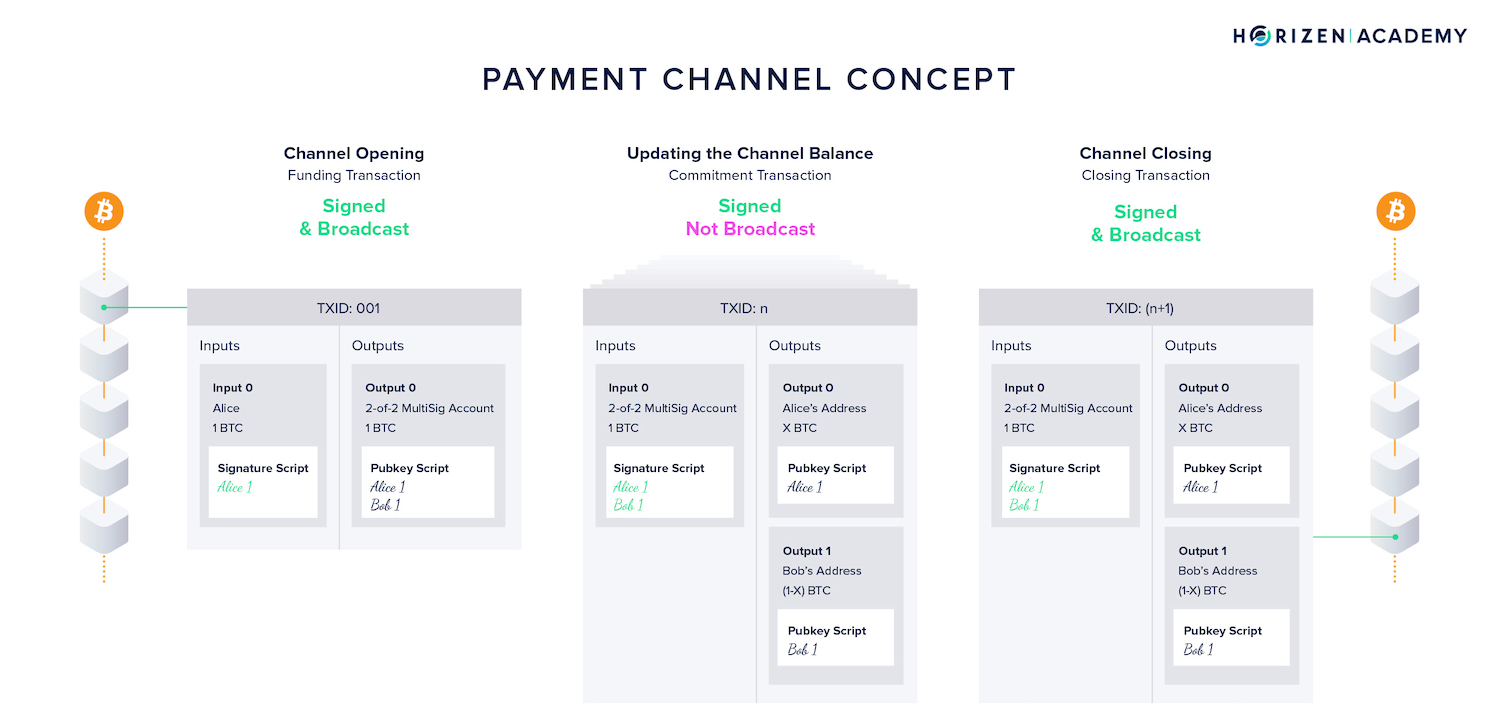

The general idea of a payment channel is the following:

- Two frequently transacting parties deposit money via a funding transaction in a 2-of-2 MultiSig account, opening the channel (

TX 001in the example below). - Both parties need to sign off on any TX that spends from this account.

- Both parties exchange signed transactions repeatedly spending from the same funding transaction whenever they transact (

TX 002-TX n).

- These commitment transactions updating the channel state, although valid on-chain transactions, are never broadcast, but kept locally by the channel participants. They serve as verifiable receipts of channel state modifications.

- Only when participants want to close the channel will they broadcast a final channel update via a closing transaction on the blockchain (

TX (n+1)).

Payment channels allow a theoretically unlimited number of bilateral transactions to occur, while only broadcasting two transactions:

- The funding TX opening the channel

- And the closing TX settling the current balance on-chain

Payment Channel Networks

Payment channel networks are built from multiple separate channels that can be coupled when needed. There are several payment channel networks built on top of different blockchain protocols, some even making protocols interoperable:

The best-known payment channel protocol built on Ethereum is Raiden. It supports the transfer of ether, as well as ERC20 tokens off-chain.

Bolt is a network proposed by Matthew Green and Ian Miers in 2016. Bolt stands for Blind Off-chain Lightweight Transactions. It is currently being considered for the Zcash protocol by the Zcash Foundation, but could also be deployed on top of other blockchain protocols.

- Bolt achieves high privacy guarantees by leveraging blind signatures and zero-knowledge proofs. To make privacy guarantees even stronger, the channel opening can be done through shielded transactions.

- The authors not only plan to deploy Bolt on Zcash, but also retrofit it to offer a private payment channel option on Bitcoin and Litecoin.

The Lightning Network is a payment channel network built on top of the Bitcoin protocol, but also deployed on Litecoin. It is the second layer network that has seen the most activity in terms of development and transacted volume.

- We use the lightning network as an example to lead you through the creation of a payment channel, updating its balance, and finally closing it.

Implementations of second-layer payment networks differ in their details. Still, the general idea remains, and by focusing on the primitives of Lightning as a single example, we can take a more in-depth look at the technology in general.

The Lightning Network - A Payment Channel Network

When you think about the Lightning network, there are two systems to consider.

- One is the Bitcoin network

- The other is the Lightning network

Both systems are circulating bitcoin by making different types of transactions. But Lightning is not limited to Bitcoin.

"Any blockchain with the necessary characteristics can plug into the Lightning Network, which means intermediary nodes can process transfers between users holding different assets in a non-custodial manner. For example, a node connected to both the Bitcoin and Litecoin networks can route a payment from a Litecoin user to a Bitcoin user via the Lightning Network." - Kyle Torpey

The Lightning Network relies on two different types of "contracts":

- Revocable Sequence Maturity Contracts (RSMCs) of which Simple Bilateral Payment Channels are realized

- Hashed Time Lock Contracts (HTLCs) which are used to connect payment channels to a network

We will pick the terms up later in this article, at a time when they will make a lot more sense to you. In the following sections, we will mostly focus on bilateral payment channels.

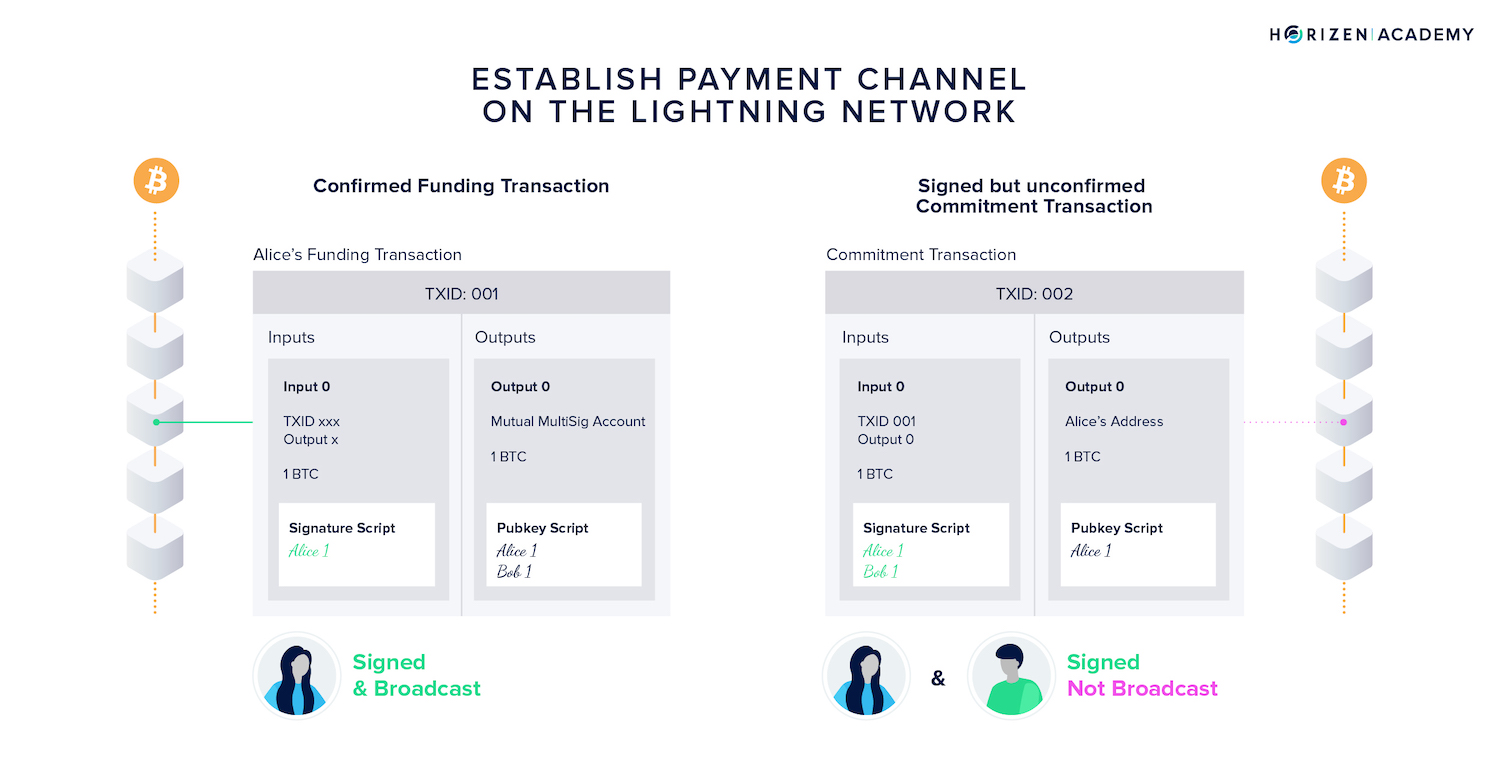

Opening a Payment Channel - The Funding Transaction

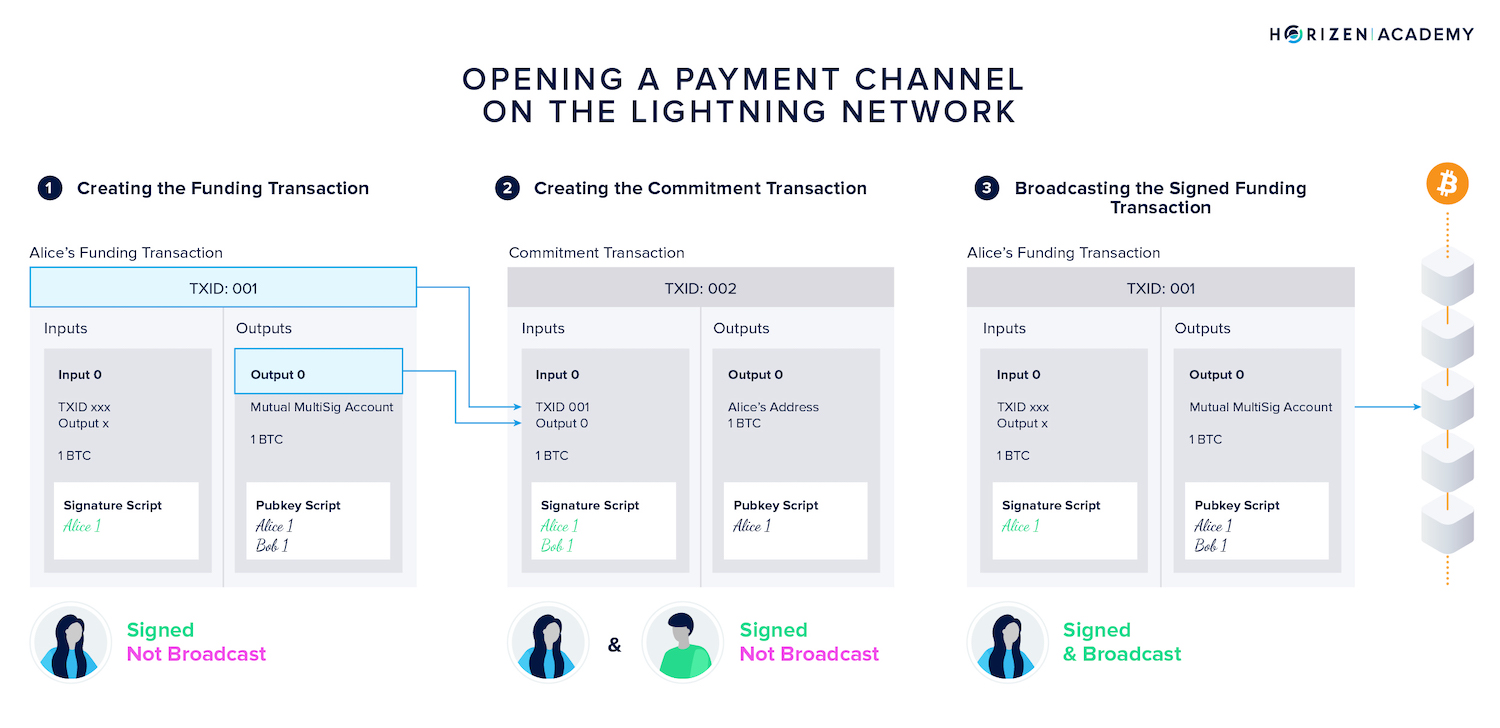

A single participant, usually the one paying the other, opens the channel by creating a funding transaction.

In our example: Alice wants to open a channel with Bob, who might have an online shop that she uses regularly.

As we already know, a payment channel is a 2-of-2 MultiSig account.

The first thing we need to ensure is that Alice doesn't lose her money when Bob becomes unresponsive. Money should not get stuck in the channel.

Unresponsiveness doesn't even have to be due to bad intentions; Bob could simply lose the key needed to sign any spending from the MultiSig.

One of the participants, in our example Alice, is funding the channel. To do so, she creates the funding transaction, signs it, but does not broadcast it yet.

Next, she uses the transaction identifier (TXID) as well as the relevant output number to create a first commitment transaction (TX 002), refunding her, and signs it.

She also passes the outpoint to Bob, who will create his version of the same transaction and sign it. The partially signed commitment transactions are now exchanged and stored locally.

Soon we will see why we need two different versions of the same TX.

Only at this point is Alice safe to broadcast her funding transaction.

She knows she can reclaim the money at any point as she already has a commitment transaction signed by Bob spending her funding TX and refunding her.

She also knows Bob cannot spend her money as both of their signatures are required to consume the funding UTXO, and the transaction she signed and passed to Bob is refunding her.

The worst-case scenario at this point is Alice paying for transaction fees sending her money on a round-trip.

The established payment channel now comprises a signed and broadcast funding transaction and a first commitment transaction serving as insurance for Alice.

Both participants sign this commitment transaction, but ideally never broadcast it, although it is a valid on-chain transaction.

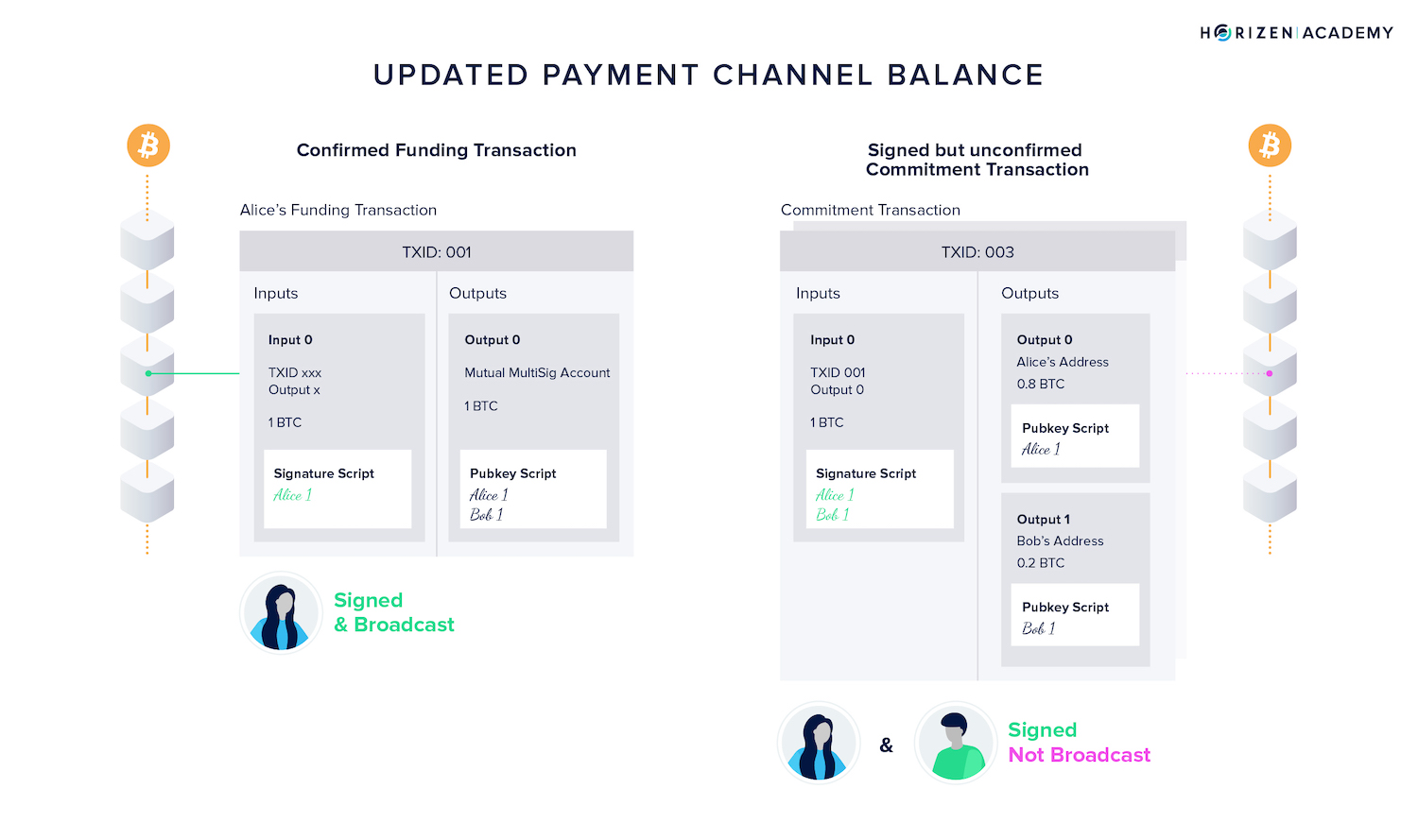

Updating the Channel Balance - Commitment Transactions

Now Alice wants to make a first transaction paying Bob, maybe because she bought something in his shop. The idea is to create a new commitment transaction, updating the channel balance.

It's important to note that all commitment transactions spend the same UTXO created in the funding transaction. This means both participants need to sign all commitment transactions, as these are the spending conditions defined when establishing the channel.

Alice wants to send Bob 0.2 BTC of the 1 BTC total.

She does so by creating a new commitment TX which now has two outputs instead of one:

- The first output acting as a change output paying her the remaining 0.8 BTC

- And a second output paying Bob.

She can sign this TX and send it to Bob for him to keep. Bob creates a TX with the same outputs, signs it, and gives it to Alice.

Now there are two versions of the same commitment transaction, each paying the participants the same amount of money. We'll get to the why in a moment.

At this point, there is a first incentive for one of the participants to cheat.

A few days after both parties agreed on the updated commitment TX, Alice has received the goods she paid for. It would be in her best interest to broadcast the first commitment TX sending her the entire money in the channel.

Bob, on the other hand, has an interest in the more recent state hitting the chain.

All commitment TXs are valid Bitcoin transactions. Although they are meant to stay on the Lightning Network, they can be broadcast on-chain.

Blockchain nodes are agnostic of payment channels and have no way to verify whether a broadcast transaction represents the most recent channel state or an old one.

In the Lightning Network, strong incentives were put in place for payment channels participants to act honestly. If Alice were to broadcast an old state, Bob would be credited with the entire balance of the channel and vice versa.

How does that work?

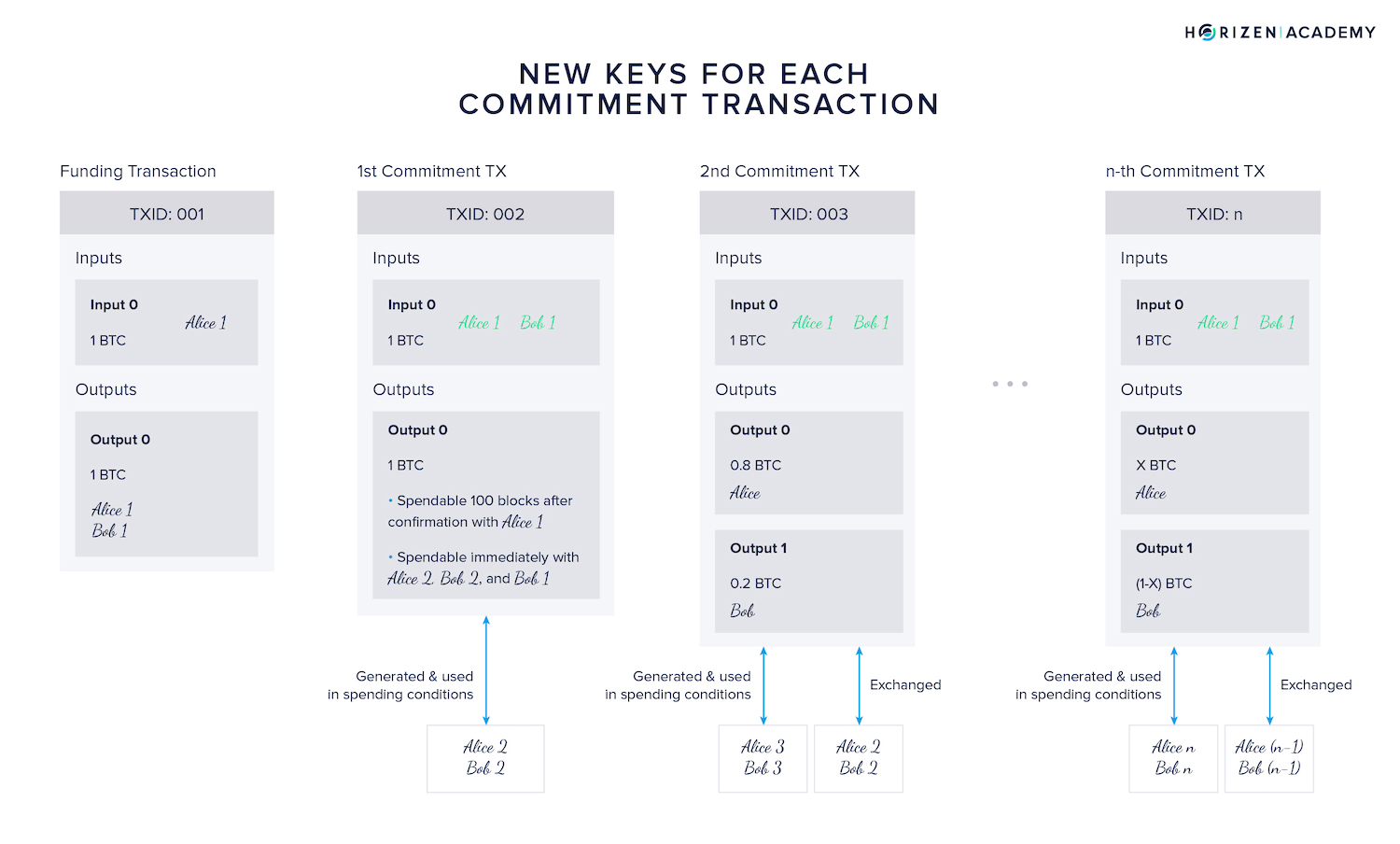

Preventing Participants from Broadcasting Old States

Here, we finally get to answer why Alice and Bob needed to create two versions of the same transactions earlier.

The tools we have at our disposal for preventing Alice from submitting an old state are the spending conditions of the commitment transaction outputs. The idea is to give Bob time to notice that Alice cheated by broadcasting an old state and providing him with a tool to claim the entire channel balance.

We combine two different mechanisms to guarantee said behavior:

- Timelocks

- and One-Time Private Keys.

Let's give Bob some time to react to Alice's cheating attempt first by introducing a timelock.

Using Timelocks in the Spending Condition

We need to make sure Alice cannot spend the UTXO created with the first commitment transaction right away if she broadcasts it.

Miners will accept the old commitment TX as soon as it is submitted on-chain. We cannot prevent the inclusion on-chain using the spending conditions. What we can avoid, though, is Alice spending the money immediately.

To do so, we place a timelock in it.

Bitcoin and most other Bitcoin-based protocols support essentially two different types of timelocks: Absolute and relative ones.

The absolute timelock CheckLockTimeVerify makes funds spendable at a defined time, like 10 pm tomorrow.

The relative timelock CheckSequenceVerify starts a countdown as soon as a transaction is confirmed.

The time unit for relative timelocks is a number of blocks, like the output might become spendable in 100-blocks time.

When a transaction output has a timelock placed in it, it adds another item to the checklist nodes will go through when validating a transaction. Besides checking whether the UTXO was previously unspent and a valid signature was presented, nodes verify if the absolute time has been crossed or if the specified amount of blocks has been passed.

The output we modify to prevent Alice from cheating is the one in the first commitment transaction: the one she would broadcast to steal Bob's 0.2 BTC.

There are two versions of this transaction:

- One created and signed by Alice and sent to Bob

- The other created and signed by Bob and shared with Alice.

We denote the version signed by Bob as TX 002A, as Alice is the one that can broadcast it (her signature is missing).

Let's assume Alice and Bob agreed to provide each other with a 10-day rebuttal-period. If one were to cheat, the other had ten days to react.

In reality, this would mean a relative timelock of 1440 blocks in Bitcoin or 5760 blocks in Horizen.

For simplicity, we will pretend we can use ten days as a time unit.

Remember, this transaction initially served as an assurance for Alice that she would get refunded in case Bob becomes unresponsive. By placing a timelock in the output, we have ensured Bob has time to react if Alice were to cheat.

As soon as Alice broadcasts the transaction, she has to wait for ten days before the output becomes spendable with her signature. If Bob notices he can go ahead and spend the money immediately using his signature.

The timelock achieved our first objective:

- Bob has time to notice the cheating attempt and react.

At the same time, it introduced a new weakness:

- Bob can take the money as soon as the transaction hits the blockchain if you look at the transaction above.

If he were sneaky, he would have Alice fund the channel and pretend to be unresponsive until she would finally decide to broadcast the transaction in an attempt to get refunded.

Now Bob could go ahead and spend the UTXO right away.

It's time to apply the second mechanism ensuring honest behavior: one-time private keys.

Using One-Time Keys to Prevent Theft

Note: For the sake of simplicity we consider private keys and digital signatures as "equivalent" in this article.

Digital signatures are generated using a private key and a message.

During the verification, the signature, public key and message are taken as inputs and the produced output is binary: Either the signature is valid or not.

Requiring Bob to simply sign-off on the TX does not protect Alice, so we expand on the second spending condition and make it a MultiSig account.

Instead of using the initially used private keys Alice1 and Bob1 in the spending condition, we use a new pair of keys generated by each participant, respectively.

These keys are generated when the first commitment TXs (TX 002A and 002B) are created, and the public keys derived from them are exchanged and placed in the spending condition.

When participants agree on the first channel update, here Alice paying Bob 0.2 BTC (TX 003), the one-time keys Alice2 and Bob2 used in the original commitment transaction's spending condition are exchanged.

At this point, Bob can be sure the transaction he already signed (TX 002A) can't be broadcast and spent immediately by Alice due to the timelock.

Alice can be sure that if Bob becomes unresponsive, she is save to broadcast the transaction because she has not shared the key Alice2 yet, and Bob can't steal the money.

This explains why it was important that Alice and Bob generated two versions of the same transaction. Remember that Bob created TX 002A. He placed the timelock in Alice's spending condition to protect himself from Alice broadcasting an old state.

Without including the second MultiSig condition, Alice would not have agreed to fund the channel in the first place. Since Bob has no interest in broadcasting the first commitment transaction, it is sufficient for Alice to place a single spending condition on her version's output.

Above, you can see the two different versions of the initial commitment TX refunding Alice. The green signature indicates which party has created and already signed it.

Going forward both, Alice and Bob will each generate a new one-time private key with every channel update and exchange the one-time keys used in the previous transaction.

Before we explained how trustlessness is ensured, we were already one step further.

Alice had agreed to pay Bob 0.2 BTC, and the keys Alice2 and Bob2 were exchanged.

The level of security we wanted to achieve is guaranteed:

- Bob has time to react (10 days) when Alice tries to cheat and can claim the entire channel balance because he can provide

Alice2,Bob2, andBob1.

One of the innovations introduced with blockchain technology was solving the double-spend problem without a central point of control.

This property is also crucial in this context, as it ensures the output in TX 002A is only spent once: either by satisfying the first spending condition - Alice timelock - or the second spending condition - Bob's MultiSig.

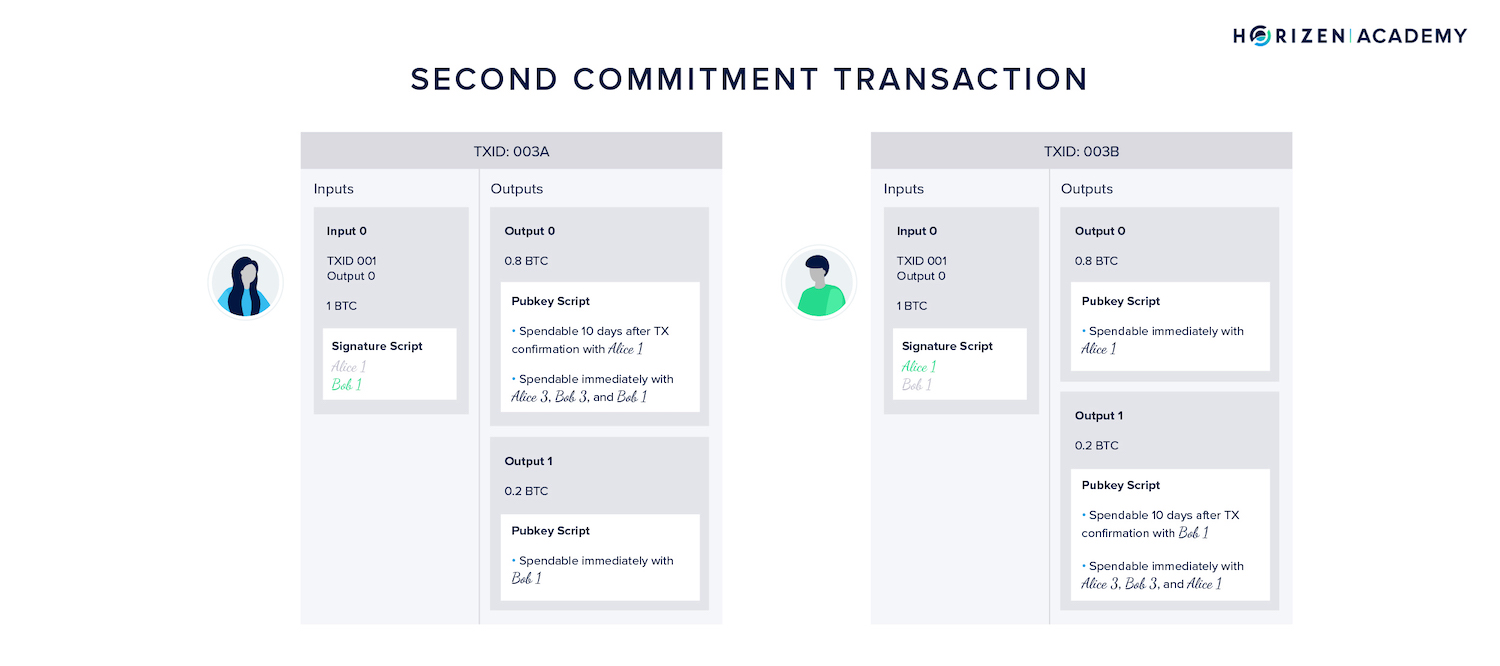

The Second Commitment Transaction

The last set of transactions we need to look at are the ones paying Bob 0.2 BTC. While we looked at the, schematically, we didn't consider the spending conditions placed in their outputs yet.

The first version signed by Bob and broadcast-able by Alice uses the same spending conditions in Alice's output of 0.8 BTC as the previous commitment TX did.

It serves the same function: If Alice made a second payment to Bob, she would again be incentivized to broadcast an old state once she received the goods.

The only difference is the updated set of one-time keys (Alice3 and Bob3) needed to satisfy the MultiSig output.

This time, Alice also secured Bob's output in TX 003B with a timelock and a MultiSig based spending condition. If the next transaction (TX 004) were paying Alice, Bob would thereafter have an incentive to broadcast an old state, and Alice is protecting herself against this.

Closing a Payment Channel

The bilateral payment channel between Alice and Bob can be closed in three ways, two of which we have covered at least indirectly:

- If no dispute occurs, both parties will agree on closing the channel mutually.

- When one party becomes unresponsive, the other party might unilaterally close the channel.

- If one party tries to cheat other and gets caught, claiming the entire channel balance via the revocation mechanism is the third and last option to close a channel.

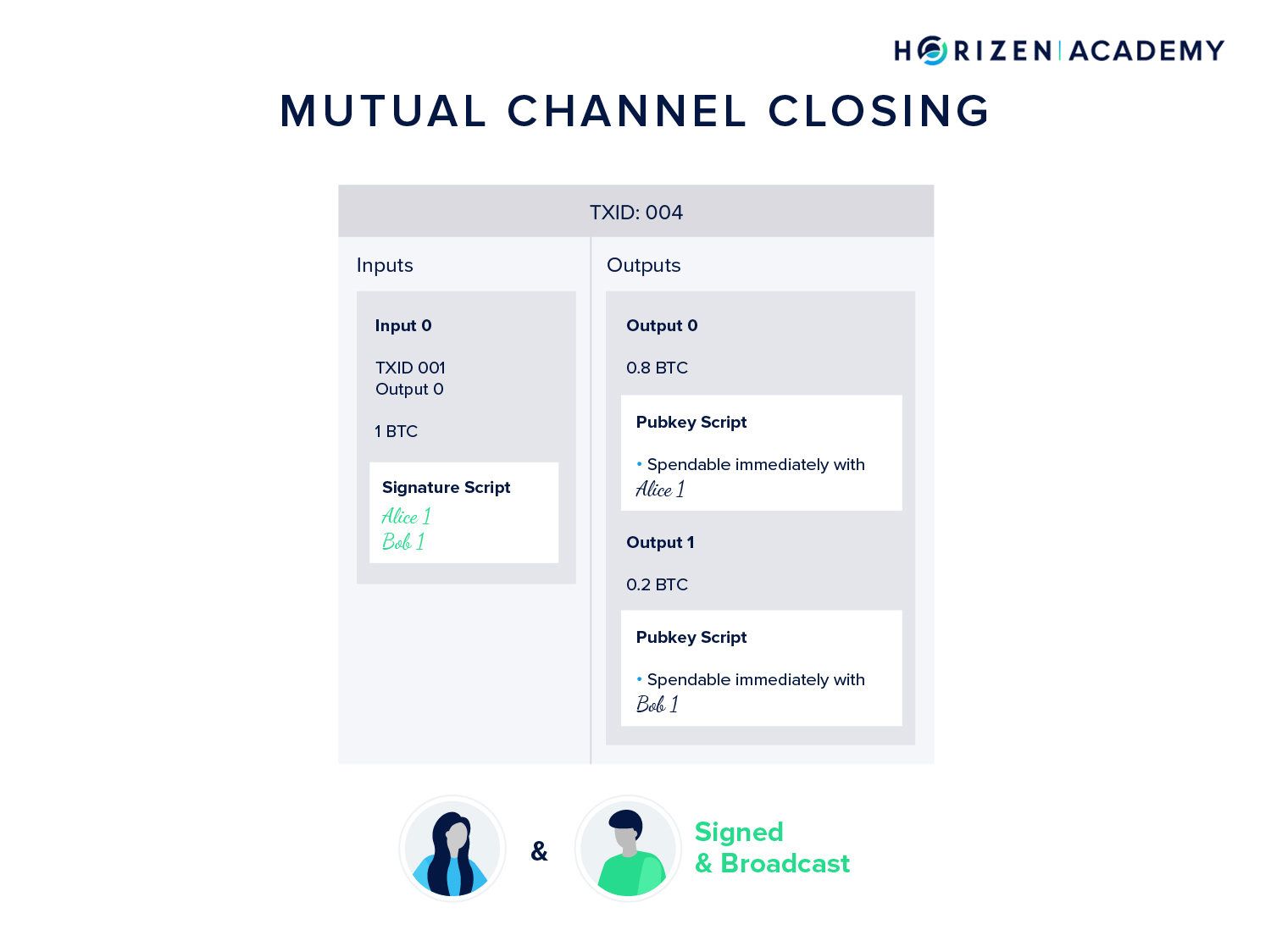

Mutually Closing a Channel

Let's assume Alice and Bob realize that they won't use their channel anymore. Both are happy with the current state of the channel paying Bob 0.2 BTC and Alice the remaining 0.8 BTC.

They will cooperatively create and sign a closing transaction, with both outputs spendable immediately by either participant.

This is the best-case scenario: No party has their money locked.

Unilaterally Closing a Channel

The second-best scenario is one of the participants broadcasting the current channel state.

The commitment transaction being broadcasted in this scenario is the one we modified in two steps:

- Using a timelock first

- And adding a MultiSig output next to prevent Bob from stealing Alice's money

This scenario is beneficial in that both parties get the amount of money that they rightfully own. The only caveat is that the party broadcasting the commitment transaction has their funds locked for whatever period was agreed upon when the transaction was created.

Revocation

The worst-case scenario, at least for one of the channel participants, is the revocation mechanism.

If Alice tried to cheat Bob, and he notices in time, he will claim the entire channel balance by fulfilling the MultiSig spending condition.

Lightning Terminology Review

Commitment transactions are sometimes referred to as Revocable Sequence Maturity Contracts (RSMCs).

- Commitment transactions are revocable as they can be replaced with more recent channel updates.

- Sequence refers to the sequence of blocks used in the relative timelock

- Maturity refers to those outputs only becoming spendable after the relative lock time has passed - the contract has matured.

The transaction granting one party the entire channel balance in case the other was cheating is called the Breach Remedy Transaction

- Breach, as in breach of a contract. Both parties agreed on only ever broadcasting recent channel states on-chain.

- Remedy as in compensating the defrauded party for said breach of contract.

While even this relatively simple composition of established features and functionalities supported by Bitcoin-based protocols allows for a handy construction, the exciting stuff happens when you connect several payment channels to a network of channels like Lightning.

To do so, we need another type of "contract" that extends the functionality of RSMCs - the Hashed Time Lock Contract or HTLC.

Hashed Time Lock Contracts - HTLCs

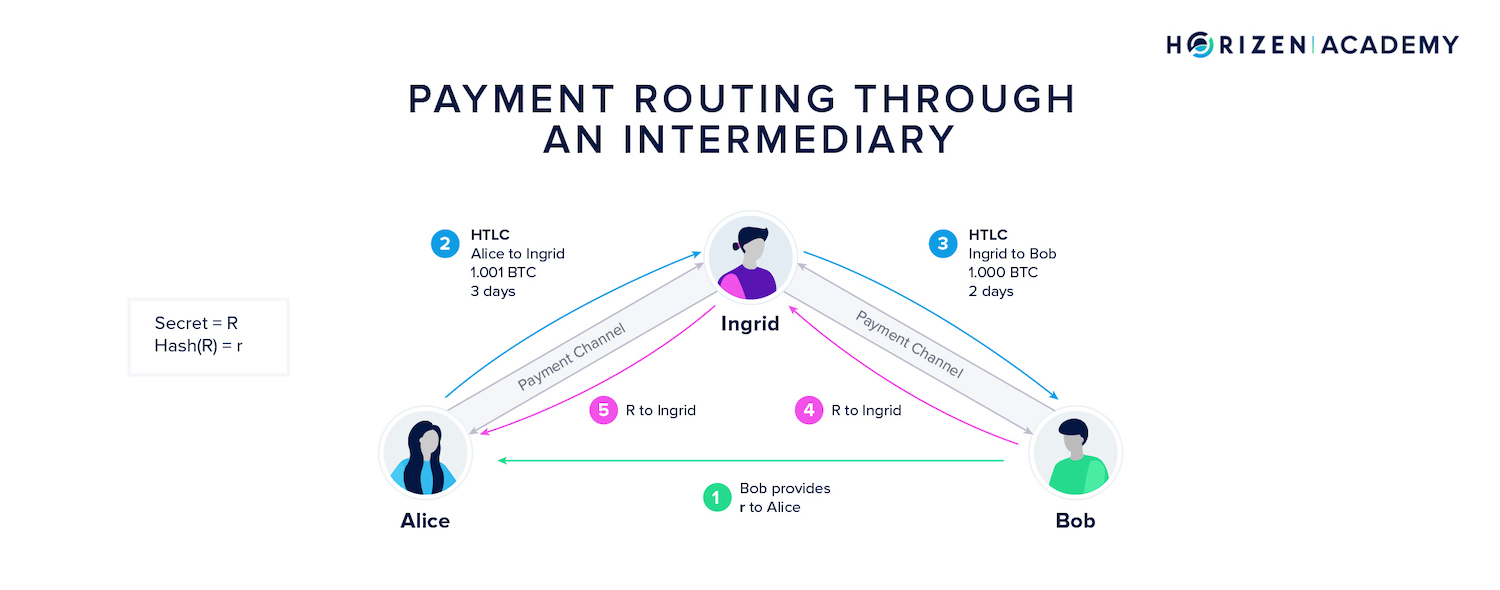

Let's consider a situation where Alice and Bob want to transact using the Lightning network but don't have an open payment channel, yet. Both do have a channel with an intermediary person, let's call her Ingrid.

Instead of opening a new channel, can't we just route a payment from Alice through Ingrid to Bob? It turns out we can, and what we need to do so is a hashed time lock contract.

But does it make sense to worry about this construction if Alice and Bob can just create their payment channel?

You can consider each participant in the Lightning network a node n, that has several connections e (from edges as they are called in graph theory) to other nodes. The number of edges needed to connect a set of nodes individually can be computed as:

To connect three nodes, you need three edges; for five nodes, you need ten edges, and for 5000 nodes, you need 12,497,500 edges.

In other words: Individual connections don't scale well.

As the name suggests, HTLCs rely on cryptographic hash functions and for the most part on two of their fundamental properties:

- Being preimage resistant one-way functions

- And mapping inputs to an ample output space making them collision-resistant.

In other words, you can't reverse a hash function, and it's practically impossible to find two different inputs producing the same output.

Building a Network with HTLCs

The general idea of routing a payment through several payment channels is to create a secret and pass the secret's hash to the payer and all the intermediaries.

If Alice were to pay Bob through Ingrid, Bob would create a secret and provide its hash to Alice and Ingrid.

Alice creates a transaction commitment) paying Ingrid, and Ingrid creates a transaction (commitment) paying Bob. The hash is part of the spending condition in each of those transactions. Revealing its preimage (the secret) allows a payee to claim the money.

Once all transactions are set up, Bob reveals his secret and claims his money from Ingrid. Ingrid learns the secret in the process and uses it to unlock Alice's transaction paying her.

The design should ensure that the intermediaries are never at risk of losing money and that funds can be retrieved from the payment route if one of the parties becomes inactive.

The timelock part comes into play as all participants need to be responsive to route the payment through the hops. Once the chain of transactions is set up, Bob has x days to claim his money from Ingrid.

She, in turn, has x-y days to claim her cash from Alice. This decreasing time lock construction ensures participants can reclaim their money if it gets stuck somewhere on the route.

Implications for the Fee Market

The Lightning Network or, in more general terms, second layer payment networks are also interesting from an economic perspective.

The transaction fees for on-chain transactions are calculated based on the amount of data a transaction takes up in the blockchain. Blocks are limited in size. Hence, miners select the transactions they want to include based on a money per data basis.

It doesn't matter if you are transferring 1 billion dollars or a single cent as long as the transaction takes up the same amount of storage capacity.

Transaction fees in a payment channel network are based on the volume of a transaction. Liquidity is the limiting factor in such a network, hence tying up liquidity is what intermediaries will base their fees on. In economic terms, they charge the time-value of money plus an amount for the counterparty risk of becoming unresponsive.

Transactions of a few cents or dollars come at almost no cost while transferring large amounts of money will come with premiums for the provided liquidity.

Currently, transacting in second-layer networks is mostly cheaper than on-chain, but once payment channel networks see more adoption, there should be an inflection point at which transactions over a certain amount of value will be cheaper to conduct on-chain where fees are based on data size.

Where this equilibrium will establish is anyone's guess today, but it will certainly be interesting to watch.

Comparing Payment Channels and State Channels

Now, there is more that you can do with blockchain besides "simple" payments. Smart contracts allow running more sophisticated logic on a blockchain, and you can run simple games on a decentralized infrastructure using these constructions.

But does it really make sense to have each move of your virtual chess game processed and verified by thousands of nodes all around the world? Scalability is an issue in blockchain-land.

With regards to throughput, it suffices to look at the events around the launch of CryptoKitties on the Ethereum network in November 2017.

It was the first dApp that gained significant traction. At some point, the dApp accounted for around 10% of total traffic on the Ethereum blockchain, causing transaction confirmation to take much longer than usual and increasing transaction fees significantly.

Many dApps don't just rely on the transfer of a token, but also the transmission of data. This data, sent to a smart contract, updates the contracts state to represent the most recent contract interactions. The idea behind more generalized state channel constructions is moving these data transfers off-chain into state channel networks where they can be performed at a lower financial and computational cost.

Just like with payment channels, only the channel opening and closing happen on-chain, while participants can transact money and data almost indefinitely while the channel is established. State channels are designed in a way that makes channel updates broadcast-able on the underlying blockchain, just like commitment transactions in payment channels represent valid on-chain transactions when broadcast.

State channels can also be combined to form networks, similar to the Lightning network.

Some notable examples of state channel projects include Counterfactual and Perun.

Counterfactual provides, besides a library for off-chain applications and a set of smart contracts, a generalized state channel protocol. The protocol aims to become a generalized framework that application developers can use to leverage the benefits of state channels without developing them from scratch. The protocol allows installing new functionalities into existing state channels without requiring on-chain transactions.

Perun channels introduce the concept of virtual payment channels over intermediaries. These channels are non-interactive in that they don't rely on intermediaries' responsiveness. The general idea is to construct virtual channels based on existing channels, which, in the end, work similarly to a bilateral channel.