What is MEV? Miner Extractable Value

Miner Extractable Value or MEV, Maximum Extractable Value for non-proof of work blockchains, has become a major topic of conversation amongst the more technical and trading focused users in the crypto space.

We explore what MEV is and how it impacts both miners/validators and users of decentralized exchanges.

What is MEV?

MEV is the process of reordering, inserting or censoring transactions within a block for the purpose of extracting additional value beyond the typical block rewards and transaction fees earned by a validator.

Non-validators, known as ‘Searches’ can also participate in MEV by identifying opportunities to front-run a transaction by paying higher gas fees to validators in order to insert their transaction first.

How is MEV Created?

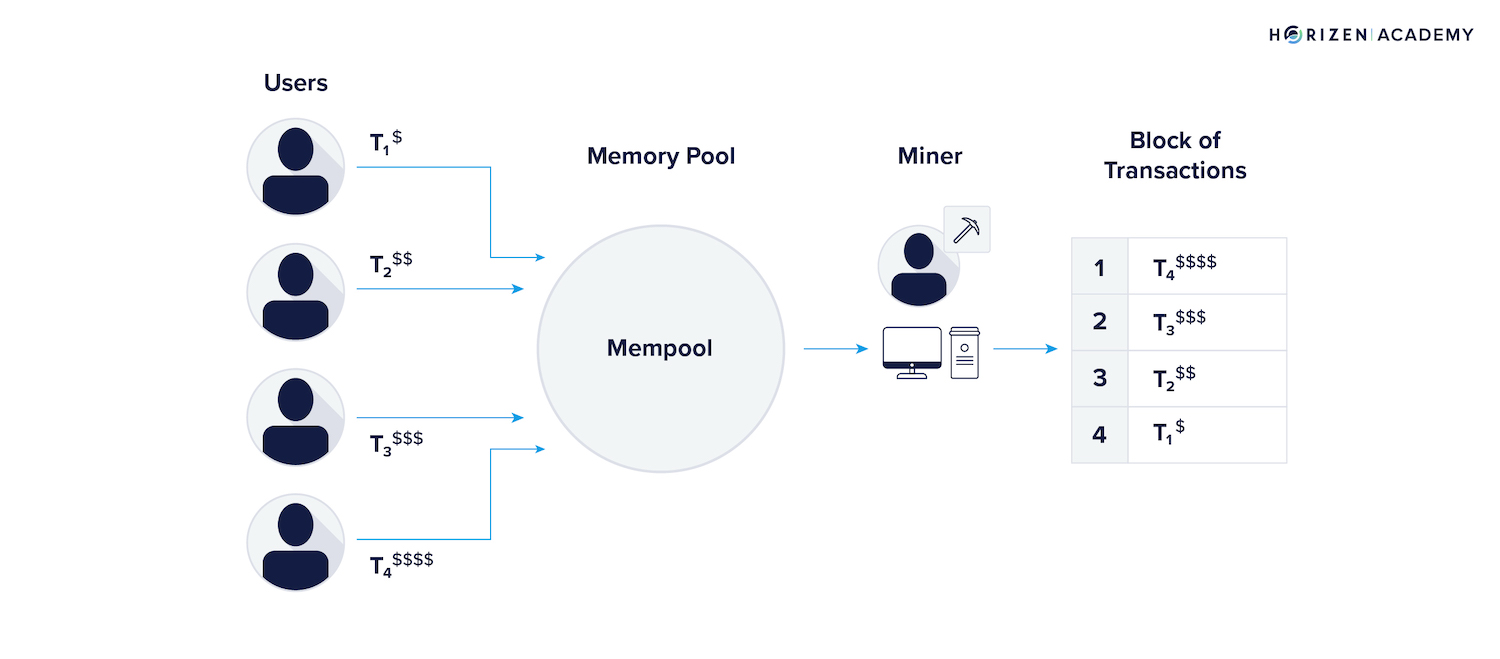

At a basic level, a blockchain is a decentralized network that consists of nodes run by validators. Validators are responsible for verifying and recording transactions on the network, and adding new blocks of transactions to the chain.

For performing this task, validators earn newly issued coins from the networks, also known as block rewards. They also earn a fee from the transactions made between participants on the network.

MEV is created because validators ultimately have a final say on which transactions get added to the next block. This means they can choose to submit transactions that include higher fees before others, enabling them to maximize their profit as a validator.

To date, over $650 million of MEV has been captured by block producers.

Another group called ‘Searchers’ can also take advantage of MEV without running a node. This is done by running bots that scan the chain for transactions of high value that have yet to be picked up by validators and submitted to the latest block.

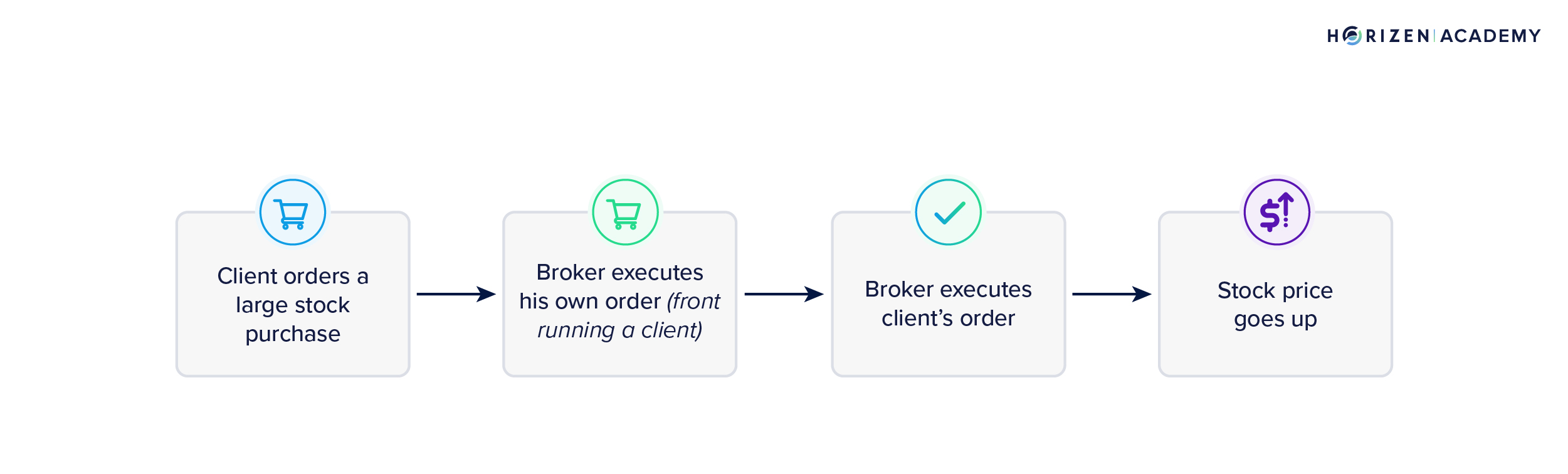

Front Running

Once a researcher identifies these high value transactions, they can ‘front-run’ them by submitting the same buy or sell order but with a higher fee in order to get them submitted first. In trading and financial markets, front running is the process of getting in front of a queue of transactions in order to get your transaction executed at a more preferential execution price.

Front Running Example

Let’s say a searcher spots a pending buy order for $1 million of ETH at a price of $1,500.

The user who submitted the transaction is offering to pay $300 in gas fees to get their transaction entered into the next block.

If the searcher wants to front run this buy order, they can quickly submit their own $1milion order to buy ETH at a price of $1,497, and pay a $600 gas fee.

Because they’re paying a higher gas fee, their transaction is more likely to be picked up by validators who are incentivized to submit transactions that will reward them with the highest fees.

The searchers transaction is submitted ahead of the first buyer and executed at a price of $1,497.

The searcher can then immediately submit another order to sell $1million worth of ETH at $1,500 and pay another $600 gas fee.

If the sell order is submitted fast enough, as in a matter of milliseconds, the searcher could end up selling their $1million of ETH to the initial buyer at their intended price of $1,500.

As a result of this front running, the searcher would have bought ETH at $1,497 and sold it at $1,500, pocketing a gain of 0.2%, or $2,000.

Once you subtract the $1,200 in total gas fees, the searchers profit is $800, not a bad outcome for a few seconds of work.

This process is also known as a Sandwich Attack because the searcher is sandwiching the buyer's transaction in between their own buy and sell order. The validator that submits these transactions to the latest block also benefits from earning the fees spent by the searchers and the initial buyer.

Risks of Front Running

Using sophisticated bots, searchers can identify similar opportunities and run these trades dozens of times each day. While front running can be highly profitable, it is not without risks.

Just because a searcher places a bid at a lower price and is willing to pay a higher gas fee, does not mean their transaction will be picked up first. There could be other searchers in the market chasing the same opportunities, which means the front-runner could themselves be front-run.

Also, the searcher could buy ETH at a lower price but be unable to sell at their desired target price due to market volatility or sell-side front running from other searchers. This could result in the initial searcher selling at a much lower price, leading to a large loss that exceeds their prior gains.

What are the Impacts of MEV?

MEV can have a significant impact on the costs that users incur to trade tokens on a blockchain network. If taken to its extreme, it can also undermine the integrity of the network, as validators begin playing the role of searchers and creating transactions that they can influence the ordering of in order to maximize profits.

MEV is enabled by the relationship between well funded traders and validators seeking maximum profits.

If there are significant profits to be made, this relationship can come at the cost of regular users who are simply trying to acquire their favorite NFT, buy tokens for use within a blockchain game or deposit funds into a lending protocol.

Invisible Tax on Users

For these users, MEV is considered to be an ‘invisible tax’ on their transactions since it costs them more to execute a trade because front-running forces them to pay a higher price for the token. This tax can become quite significant during periods of high volatility, such as the minting of a popular NFT or the launch of a blockchain game.

These moments are prime opportunities for validators and searchers to maximize profits from MEV while regular users are less price sensitive.

The question of whether MEV is good or bad is still up for debate. Some consider it to be unethical for validators to reorder transactions in order to extract higher fees or for searchers to purposely pay extremely high fees just to front run an order.

Others argue that it is just a normal part of free markets. Front running is a normal occurrence within the traditional stock market. It is a primary method in which high frequency trading firms achieve their edge in the market. Unlike hedge funds, HFT firms optimize for speed of trade execution.

This allows them to generate above market returns by executing millions of transactions a few milliseconds before their competitors in order to buy at a cheaper price and sell at or above the market price. With high-frequency trading, the general direction of the market rarely plays a significant role in decision making.

Regardless of what one thinks about the ethics of MEV, what can’t be denied is that the spoils of MEV tend to accrue towards those participants who have the most technical capability and information asymmetry. While it may not be entirely possible to stamp out MEV, some blockchains have developed ways to make the regards from MEV more evenly distributed towards users of the network - we can think of this like a refund on the invisible tax that users incur.

The benefits that accrued through this practice can be significant, albeit unevenly distributed amongst participants in the network. Only those who have a high degree of technical capability and information asymmetry can reap the benefits of MEV.

Solutions to the MEV Problem

To solve this problem, Flashbots, an Ethereum research organization, is developing an ‘MEV Boost.’

MEV Boost solves the problems of MEV in the following ways:

- Quantifying the scale and volume of MEV extraction

- Democratizing access to MEV profits

- Reducing the impact of MEV-related transactions on everyday users

The approach of MEV Boost is to separate the role of a validator into 2 functions: proposers and builders.

In the Proposer-Builder Separation or PBS model, validators receive bids from entities tasked with assembling blocks of transactions and then choose which block to propose to be added to the chain.

Through a ‘commit-reveal scheme’, proposers could be prevented from accessing the contents of a block before signing it, thereby removing the incentive for validators to reorganize transactions or collude with searchers.

MEV Boost also makes it possible for validators to distribute MEV rewards from a block to its pool of stakers, which can incentivize individual token holders to want to stake their tokens to that pool.

These are some of the early approaches that are being researched and tested in order to increase the net positive impact of MEV on blockchain networks.